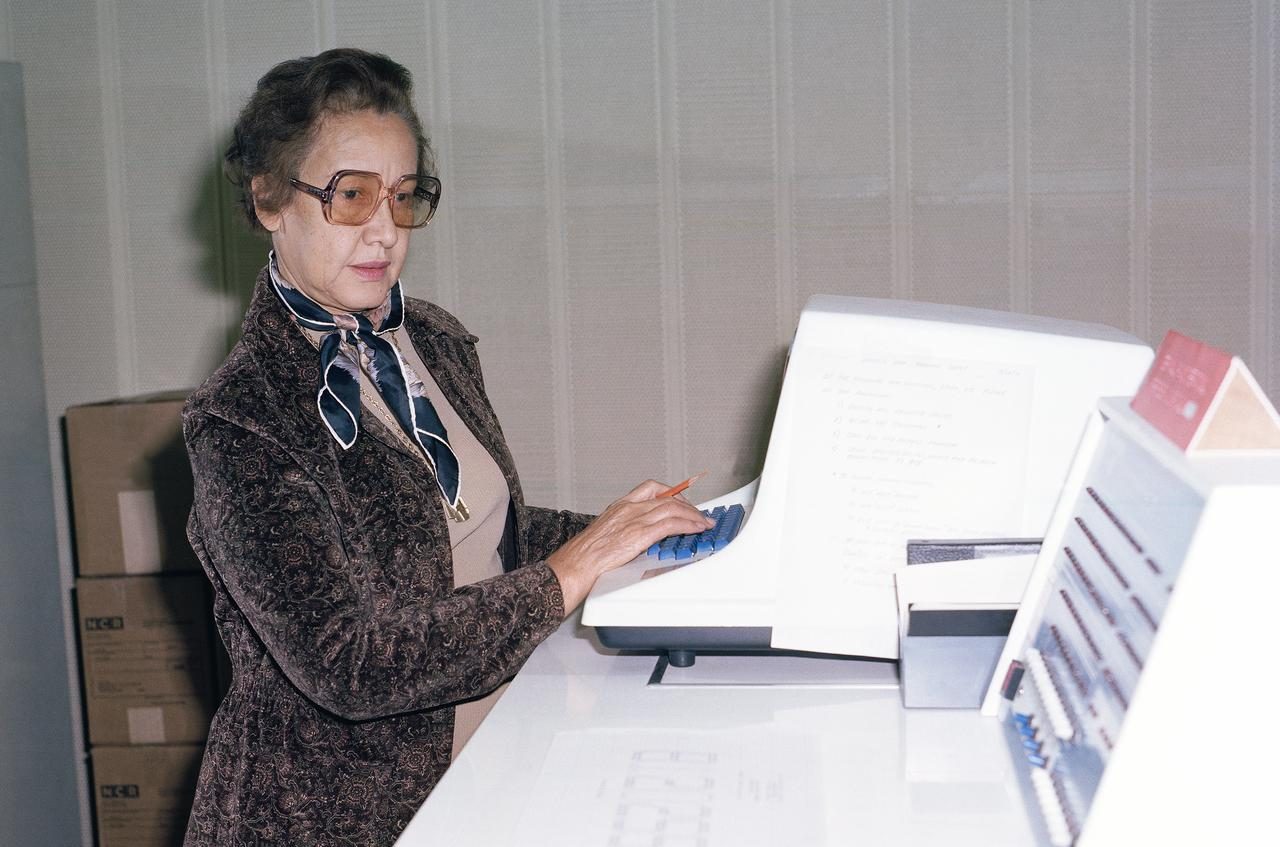

Katherine Johnson was a leading light at NASA and an indispensable part of its early space exploration programs. She died on Monday, Feb. 24, 2020.

Before there were mechanical computers, there was Katherine Johnson. Her mathematical prowess helped keep astronauts safe and on course during Mercury, Gemini and Apollo missions. Armed with nothing more than a pencil, a slide rule and her brain, Johnson earned the trust of the first astronauts like John Glenn and Alan Shepard.

Born in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia in 1918, Katherine Johnson’s intense curiosity and brilliance with numbers vaulted her ahead several grades in school. By thirteen, she was attending the high school on the campus of historically black West Virginia State College. At eighteen, she enrolled in the college itself, where she made quick work of the school’s math curriculum and found a mentor in math professor W. W. Schieffelin Claytor, the third African American to earn a PhD in Mathematics. Katherine graduated with highest honors in 1937 and took a job teaching at a black public school in Virginia.

Johnson joins space race

Johnson found out that NACA, the precursor to NASA, was looking for people to join the all-black West Area Computing section at the Langley laboratory, headed by fellow West Virginian Dorothy Vaughan. She began work there in 1953, beginning a 33-year career with NASA that included work on the Mercury, Gemini and Apollo programs.

The group Johnson joined, the West Area Computing section, wasn’t what we think of in modern terms when we hear the word “computer.” They were a group of women who could perform complicated mathematical calculations for the engineers planning missions to space.

In 1957, Katherine provided some of the math for the 1958 document Notes on Space Technology, a compendium of a series of 1958 lectures given by engineers in the Flight Research Division and the Pilotless Aircraft Research Division (PARD). Engineers from those groups formed the core of the Space Task Group, the NACA’s first official foray into space travel, and Katherine, who had worked with many of them since coming to Langley, “came along with the program” as the NACA became NASA later that year.

She did trajectory analysis for Alan Shepard’s May 1961 mission Freedom 7, America’s first human spaceflight. In 1960, she and engineer Ted Skopinski coauthored Determination of Azimuth Angle at Burnout for Placing a Satellite Over a Selected Earth Position, a report laying out the equations describing an orbital spaceflight in which the landing position of the spacecraft is specified. It was the first time a woman in the Flight Research Division had received credit as an author of a research report.

John Glenn’s respect

In 1962, as NASA prepared for the orbital mission of John Glenn, Katherine Johnson was called upon to do the work that she would become most known for. The complexity of the orbital flight had required the construction of a worldwide communications network, linking tracking stations around the world to IBM computers in Washington, DC, Cape Canaveral, and Bermuda.

The computers had been programmed with the orbital equations that would control the trajectory of the capsule in Glenn’s Friendship 7 mission, from blast off to splashdown, but the astronauts were wary of putting their lives in the care of the electronic calculating machines, which were prone to hiccups and blackouts.

As a part of the preflight checklist, Glenn asked engineers to “get the girl”—Katherine Johnson—to run the same numbers through the same equations that had been programmed into the computer, but by hand, on her desktop mechanical calculating machine. “If she says they’re good,’” Katherine Johnson remembers the astronaut saying, “then I’m ready to go.” Glenn’s flight was a success, and marked a turning point in the competition between the United States and the Soviet Union in space.

For her pioneering efforts, Johnson received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Obama in 2015. Together with the Congressional Gold Medal, this is the highest award given to a civilian. Johnson is just the second woman to get the prestigious honor, along with pioneering astronaut Sally Ride.

Celebrating Katherine Johnson’s life

[envira-gallery id=”33746″]

Our @NASA family is sad to learn the news that Katherine Johnson passed away this morning at 101 years old. She was an American hero and her pioneering legacy will never be forgotten. https://t.co/UPOqo0sLfb pic.twitter.com/AgtxRnA89h

— Jim Bridenstine (@JimBridenstine) February 24, 2020

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by William T. Harris (@spacecenterhou_ceo) on Feb 24, 2020 at 8:34am PST