Astronaut Friday is a way for us to explore the biographies of astronauts who you may not know much about. There may be a movie coming out about Neil Armstrong, and Buzz Aldrin may have a Twitter feed, but do you know much about Apollo era astronaut Walt Cunningham? The 50th anniversary of Cunningham’s Apollo 7 mission will be Oct. 11, so let’s explore his storied NASA career.

1) Induction to National Aviation Hall of Fame

On Sept. 28, Cunningham was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in Washington, D.C. Cunningham served as a fighter pilot during the Korean War. He reached the rank of Colonel in the Marine Corps during his time there. Cunningham actually joined the Navy first in 1951 but was commissioned into the Marine Corps in 1953 after going through flight training.

He flew 54 combat missions during the Korean War. “In the Navy, in those days, you ran the risk of being assigned to torpedo bombers or transport pilots,” Cunningham said in a 1999 interview with JSC historian Ron Stone. “And the Marine Corps guaranteed you that your first tour, you would be flying single-engine fighter planes.”

Cunningham flew in three different squadrons, including VMF-513 (Marine Attack Squadron), VMF-542 (Marine Night Fighter Squadron) and VMF-134 (Marine Fighter Attack Squadron) in the 1st Battalion of the 23rd Marine Regiment. He served from 1953 through 1956 when he went into the Reserves. As part of VMF-542, Cunningham flew the Douglas F3D Skyknight, a plane specifically designed to detect and fight enemy planes at night. Though he served for three years, Cunningham didn’t see any real firefights. The Korean War ended July 27, 1953.

“I was in the last squadron that had a mission in Korea, but we did not ever see any combat,” Cunningham told Stone. “We got to chase a couple of these ‘bed-check Charlies,’ little light airplanes flying around at night. Tremendous competition and a fight to go—to see who would get launched just to shoot down anything that you could!

“I was flying night fighters at the time, and we would have—one might be having dinner at the Officers’ Mess there, and we’d get a—the alarm would go off, and we’d have an alert. And we always had somebody on strip alert. They would launch, and we all would fight and run a half mile down there to see who would be the next airplane in line, just so we’d get a chance to shoot. Never shot at anything ever.”

Cunningham was the second Marine to go into space, following John Glenn. In that same oral history, he laments not being able to fly fighter jets.

“I have not really done hardly any flying in the last 20 years, and yet I cannot hardly stand today to look up, especially in bad weather, and hear a T-38 going through the clouds up there,” Cunningham. “It honestly hurts.”

2) He was the third civilian astronaut

Every member of the Mercury 7, NASA’s first group of astronauts selected in 1959, was an active member of the military. Three were Air Force, three were Navy and one was Marine Corps.

The second group, selected in 1962 and collectively known by the less catchy nickname The New Nine, featured the first two “civilian” astronauts in Neil Armstrong and Elliot See. Both had previously served in the armed forces, but were not actively serving at the time they were selected. Armstrong was a naval aviator during the Korean War before mustering out and becoming a test pilot for NASA’s predecessor, National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA). See served in the Navy Reserves before being called up to active duty during the Korean war.

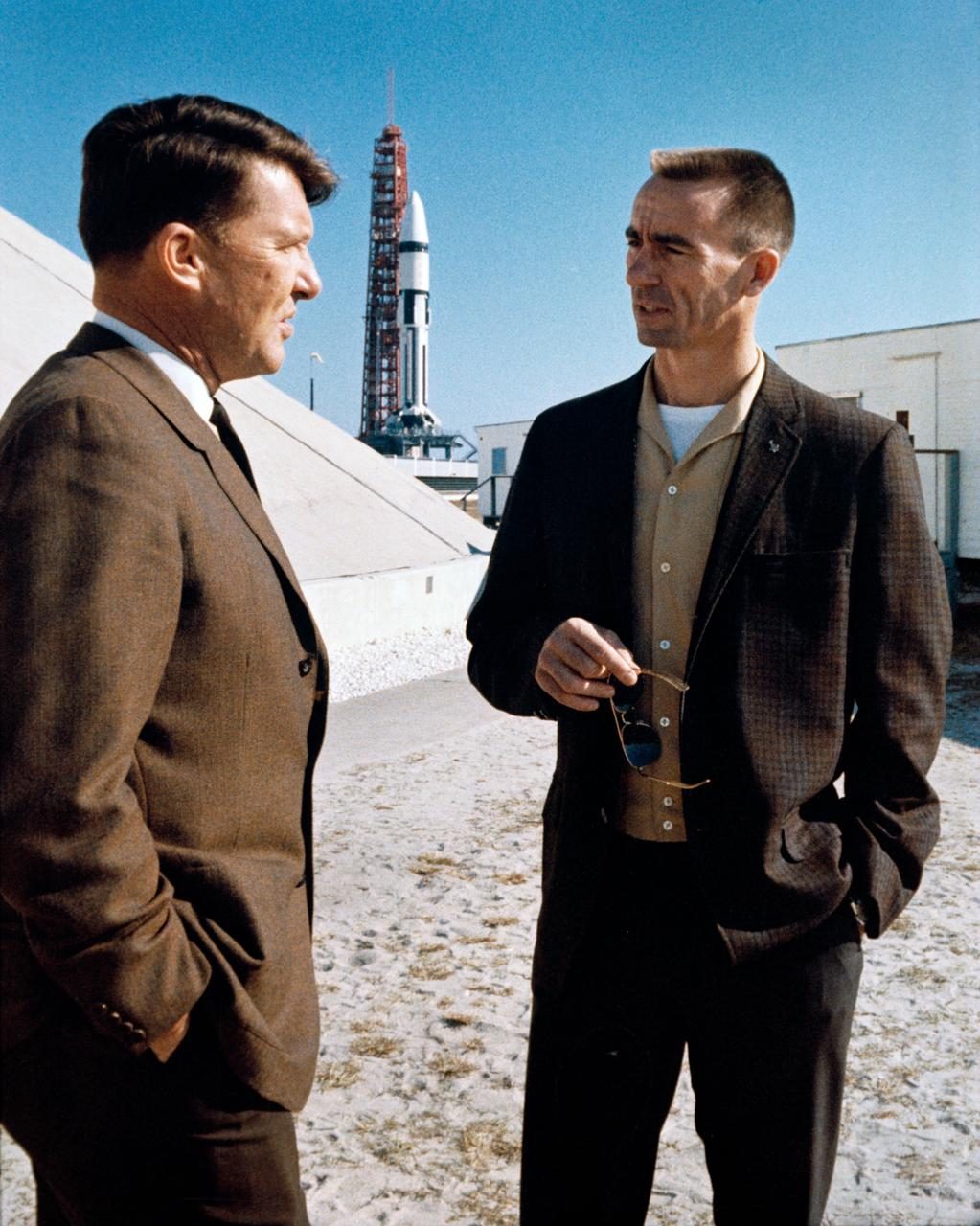

Group Three, selected in 1963, featured just Cunningham as the “civilian” astronaut. NASA had waived its requirement of being a test pilot for this group; instead, they required military jet fighter experience, which Cunningham had. He also had extensive college work, getting his Ph.D. in physics, similar to the path Buzz Aldrin took. While he was finishing his degree, Cunningham didn’t expect to one day go into space.

“I was driving over Mulholland Drive and down into Santa Monica,” Cunningham told Stone. “And I was listening. It was just before 10 o’clock in Florida, and it was just before 7 o’clock in California; and as it got down to the last 4 or 5 minutes of the countdown, I was so excited that Alan Shepard was about ready to be launched that I couldn’t drive anymore! I pulled over to the side of the road and I listened. And they got to the final count: 3 – 2 – 1 – liftoff. And before that Redstone rocket had cleared the tower, I heard myself yelling out loud and didn’t even realize it. I says, “You lucky son of a bench!” And later, I realize that that’s kind of when it changed from being just a generalized envy to a real desire to go down and do that job. And 2 years later, I was sharing offices with that same Alan Shepard.”

Making the decision to become an astronaut and actually being selected are two different things, but Cunningham pushed on with the same determination that he did everything else.

“I think I had a little bit stronger academic skills, which helped a bit. I had, you know, great recommendations on flying. But some of these guys had been flying—half of them were test pilots. I had never gotten to Test Pilot School. They’d been flying later-model airplanes. I’d been in the Reserves. The Regulars all on active duty kind of looked down their nose at the Reserves. They could’ve looked down their nose at me because I was studying physics instead of being an engineer. That kind of thing. So, I remember feeling that I might be a long shot.

“There were 28 of us left in the running. We didn’t know how many they were going to select—yet. And a couple of weeks later, we showed up for final interviews (and this was in person, 3 or 4 days). And I got to see some of the people that I had not seen during the physical selection. They were even more impressive! And they all seemed to know these guys personally, you know.

“The other guys, some of them had been through the selection a couple of times; and they knew these guys, too. And so, I felt like, when the upshot—when it was all over and I was one of the 14, I thought I had been very fortunate to make it through the competition.”

3) Apollo 7 was the first three-person American space mission

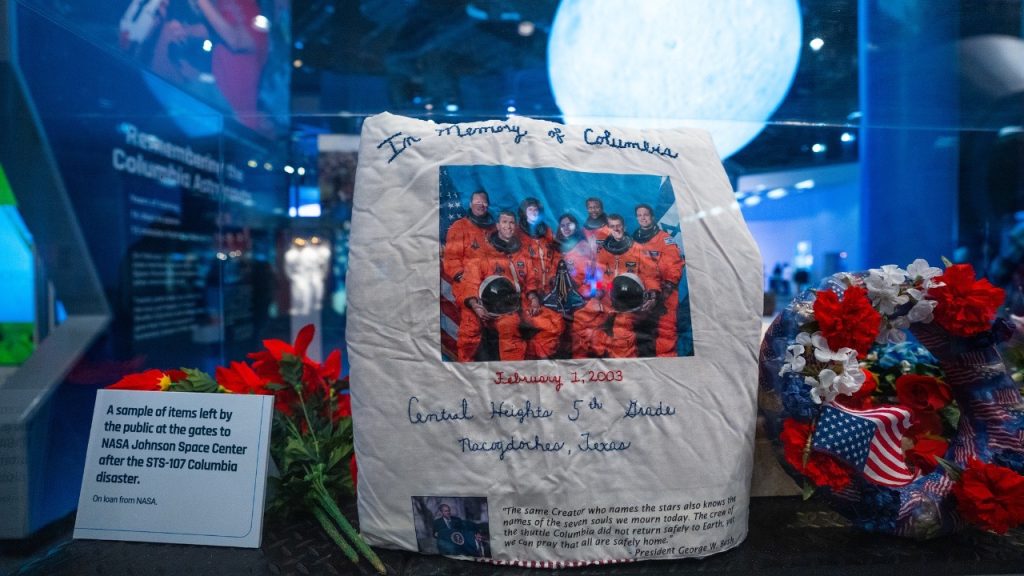

After the devastating Apollo 1 fire claimed the lives of Gus Grissom, Ed White and Roger Chaffee, NASA didn’t send a crewed mission into space for 21 months. The mission to break that streak was Apollo 7. It was a shakedown cruise around Earth. The mission didn’t feature a Lunar Module, but it did last 11 days, longer than the astronauts would need to be inside on a trip to the Moon and back.

It was also the first official NASA mission to feature three crewmembers. Cunningham was joined by commander Wally Schirra and Donn Eisele. Shirra was one of the Mercury 7 and made his third and final trip into space on the mission. Eisele’s lone mission into space was part of Apollo 7. Cunningham and Eisele were both scheduled to be on the crew for Apollo 2 before that mission got cancelled after the Apollo 1 tragedy.

“Wally really was ready to leave the space program,” Cunningham told Stone. “He’d flown Mercury and Gemini. He wanted to go off and become a millionaire and planned on leaving. Deke Slayton, who had been grounded with his heart problem, continued to want to fly; and later, I came to realize, but this was supposed to be Deke’s flight because it was not a critical flight. Apollo 1 was important. Apollo 2 was almost a redo of the same thing, plus it had the science on it. And if Apollo 2 didn’t work, it wouldn’t be too bad to have a guy who had a heart problem on Apollo 2—whereas it would’ve been on Apollo 1. So, Deke wanted to have that flight. Eventually the powers that be wouldn’t approve Deke to do it. And he had prevailed in the meantime on Wally to stand in for him. Wally wasn’t serious about training or anything, and Donn and I, being rookies, you know, we ate up everything. We wanted everything to be absolutely correct. Well, eventually they said ‘No’ to Deke. Wally was stuck with this flight.

“Apollo 7 became very important. It was—if we had not had a success on Apollo 7, we really don’t know what would’ve happened to the space program. Another accident and the fainthearted in the country, as we have a tendency to be, would’ve been clamoring to stop it, you know. Apollo 7 became very important. We were proud to be assigned the mission, and Wally’s attitude was entirely different. It was important. It was to save the space program. It became known as “Wally’s mission.” I mean, Donn and I hardly even existed in the eyes of the media. And Wally warmed to the task. There was still a lot of work. Wally was not the world’s greatest nose-to-the-grindstone guy, but he began to realize that this was important and he wanted it to be successful.”

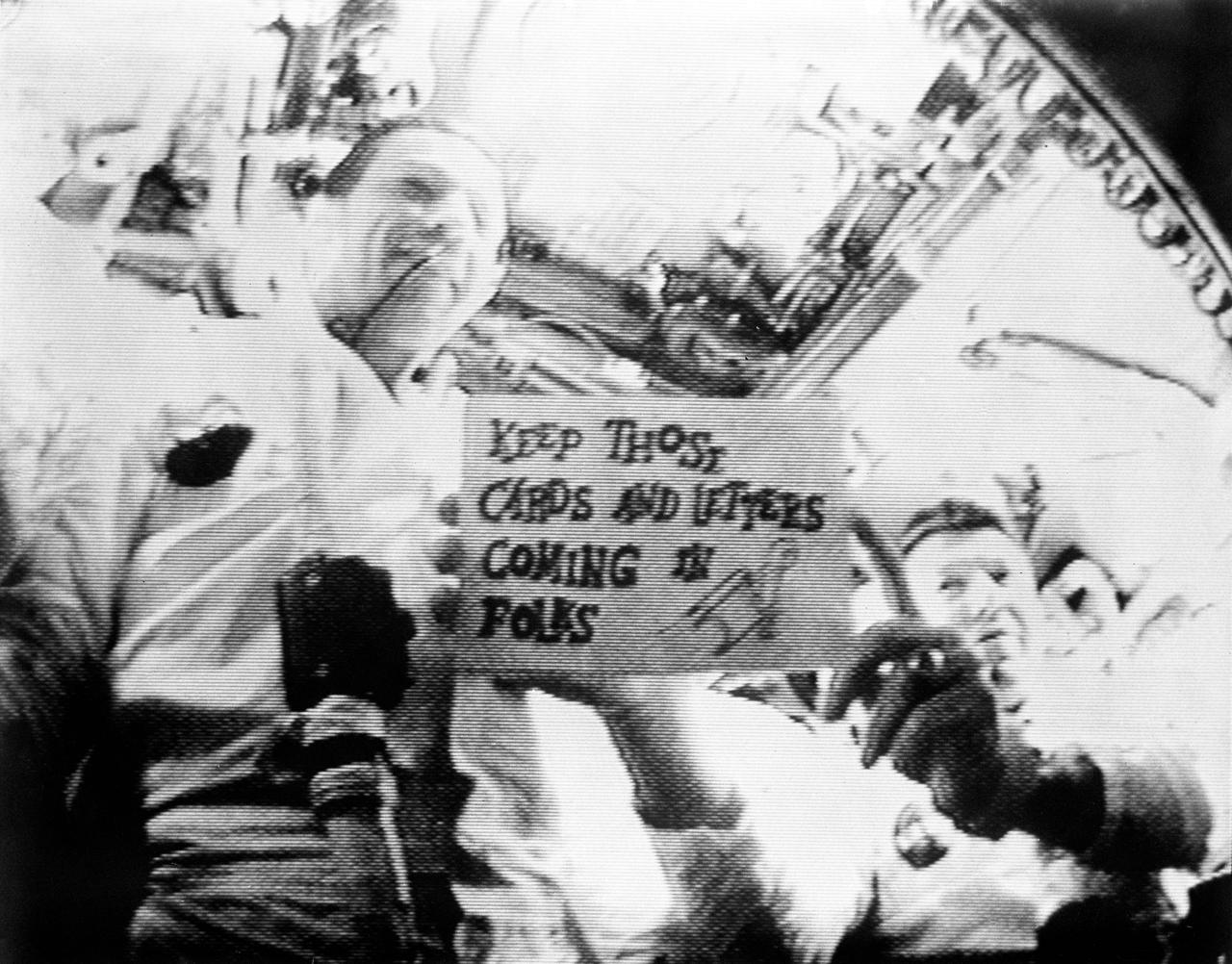

Apollo 7 was a successful mission, giving NASA’s engineers plenty of data on how to better make ensuing Apollo missions more efficient and effective. For instance, a simulated Lunar Module rendezvous was made more difficult by one of the panels not completely deploying. That led to engineers making the panels jettison completely on subsequent flights.

However, tensions rose within the crew once Schirra developed a head cold. The cold made him irritable, something he took out on Mission Control. That “insubordination” meant that none of the three crew for this flight went to space again.

“There was some real bickering back and forth between Wally and the ground,” Cunningham told Stone. “I, frankly, have never felt like I had any kind of a problem with the ground, with going over the onboard tapes and air-to-ground and what have you. Donn, a little bit. But Wally was still demonstrating that it was Wally’s flight and Wally was in charge. He has maintained since, that he felt the responsibility. He’s never said that what he did was anything except the responsible thing to do, but he’s maintained he carried that responsibility because [he] didn’t want to have anything else happen. I really think it’s a case of, on some instances, Wally wanting to insist he was in charge when nobody cared who was in charge anyway.

“I think that it was the prima donna in Wally coming out. I think it was that he did feel pressure with the responsibility. I think he felt like he was getting old for the business, you know, he always said that this business will—is—it kills you slowly. I mean, it just takes everything out of you. I also think that Wally was not as well prepared for the flight as a lot of other people have since been. So, it—things were new to him. He was discovering things for the first time on the mission.”